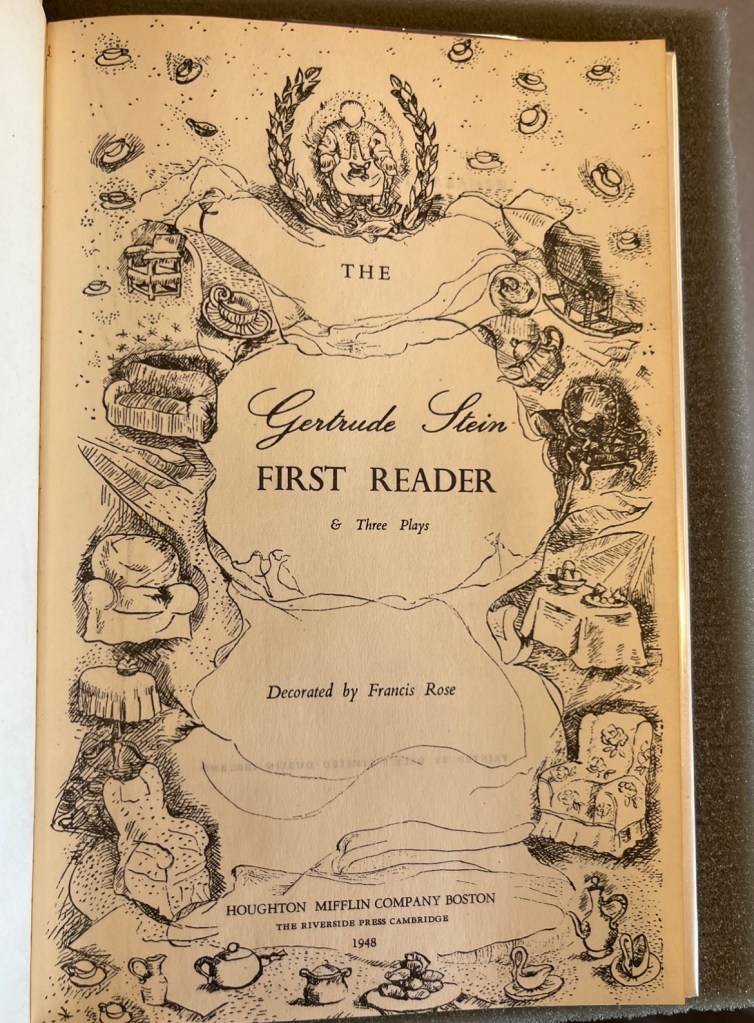

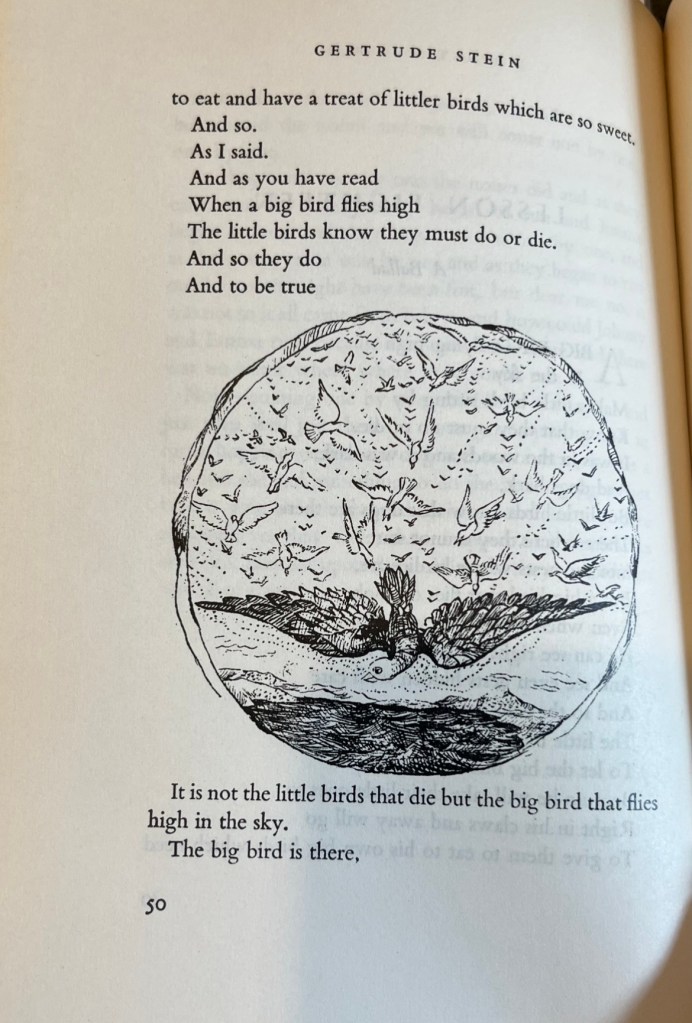

In 1946, the artist Francis Rose completed a series of drawings to be included in The Gertrude Stein First Reader & Three Plays, by Gertrude Stein, which was first published in 1946. Three of these sketches are preserved in the Robert A. Wilson collection of Gertrude Stein materials at Johns Hopkins University. Two of these three (fig. 1 and fig. 2) made it into the final publication of the work. The third, and our focus for this post, did not (fig. 3). Completed in the same year as Stein’s death, the sketch asks more questions than it can answer about Stein’s vision for her publication and her professional relationship with her friends. The basic facts about the drawing remain known to us from the archive: the creator, the date of creation, and the intended purpose. But these three facts only lead to more questions about the context of the making of the work and the preservation of it. Why was this particular sketch discarded from the publication, yet preserved in the archive, and what can that tell us about Rose’s involvement with First Reader?

Stein recounts beginning of her friendship with Francis Rose in the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. She had collected some thirty odd pieces by him before finally meeting the man in Paris in 1931, through her other artist friend, Álvaro Guevara (284, 308). A friendship quickly bloomed. Rose visited Stein and her partner Alice Toklas at their summer home in Bilignin and painted both women’s portraits; the portrait of Toklas is included in the Autobiography. Their friendship remained steadfast through the end of Stein’s life and he and Toklas remained in communication long after Stein’s death in 1946.

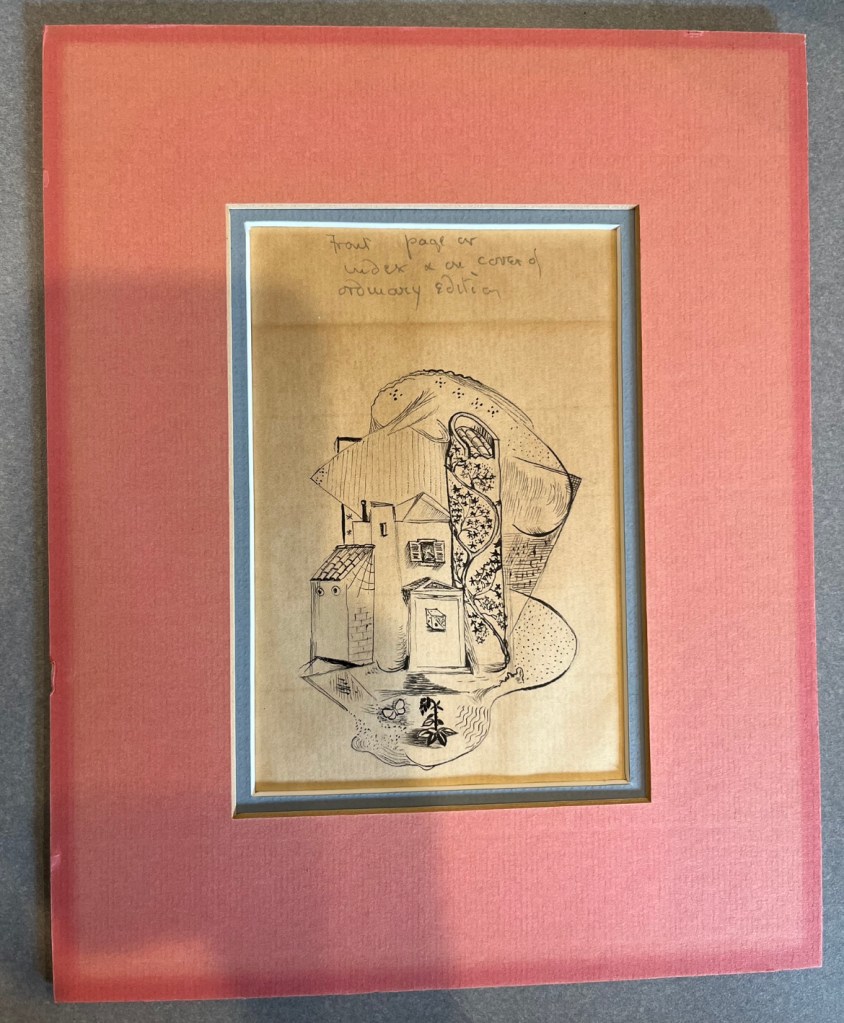

The small sketch in question features a disjointed house with a winding tower of sorts, covered in vines. A butterfly sits next to a leaning flower in the front yard of the house. The scene is spliced together, reminiscent of Picasso’s early experiments with cubism. “Front page or under [] cover of [ordinary] edition” is written in faint pencil at the top. This suggests that there were multiple editions planned following a hierarchy – a deluxe version as well as an ordinary one. The sketch is mounted on a red and blue cardboard frame and backing, the colors faded with age. What do these visual cues tell us about the history of this object that is missing from the archive?

Someone cared enough to mount and preserve this piece, ensuring that future generations could look at it. Was it Rose himself that did so? Was this sketch (and its two companions) in Stein’s possession before her death?

Let’s consider the pencil at the top of the drawing. Rose clearly intended this piece to be front and center of a book – either on the cover or potentially on the inside cover page. He also intended it to be used in a specific edition. Perhaps this sketch does exist in printed form for the First Reader, just not in this archive – perhaps not in any archive. The largest collection of Gertrude Stein materials at the Beinecke Library at Yale University has seven artworks by Rose, but none are specifically drafts for illustrations in Stein’s books; these pieces tells us little about the process of getting Rose’s illustrations into print.

First Reader was published in November of 1946 by Maurice Fridberg in Dublin, complete with Rose’s illustrations. Stein passed in July of that same year. How involved with the publishing process had she been? Did the final version reflect her vision for the book? Given that Stein was dealing with a serious illness during the final year of her life, how did this collaboration between Stein and Rose function? Did she ask Rose to illustrate, or did Rose offer? Two years later, in 1948, Houghton Mifflin Company published the book in Boston, also illustrated by Rose (fig. 4 and fig. 5). This is the version available through the Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins. From what few online images I could find of the 1946 edition, it appears to have the same internal illustrations as the 1948. However, without fully examining a physical copy I can’t be sure. Does this missing publication contain our sketch? None of these questions can be answered through the visual material alone or through Robert A. Wilson’s collection alone. We do know that the drawing was made in 1946, yet if it was completed before or after Stein’s death is unknown.

The Beinecke Library’s collection contains correspondence between Toklas and Rose between 1946-1955. These letters are not digitized, so for the moment, I do not know what they might contain. It’s possible that he and Toklas communicated about the publication of the First Reader after Stein’s death and these letters hold clues to the fate of this sketch. Rose also illustrated Toklas’s cookbook, published in 1954, so the correspondence may have focused on that collaboration instead.

Francis Rose never reached the level of notoriety as many of Stein’s more famous friends. He is most frequently identified through his relationship with the author, although his artistic achievements go beyond the time they spent together. This relative lack of fame makes finding information about his artistic practices and publications as an illustrator difficult; although he published a memoir of his life in 1961, titled Saying Life, the veracity of the stories is questionable (the book has been nicknamed Saying Lies).

An entire collection consisting of correspondence, early drafts for the books, drafts of the illustrations, and more could be formed around this one object and this one publication – such is the limit of an archive. Only a finite number of materials can be preserved through the unfortunately limited resources of many libraries, and those must first be deemed important enough to save by both creators and collectors – to compile all the evidence that a researcher may need to answer one single question in one place is near impossible. There is a whole trail of material leading up to the creation of this drawing and a whole trail of materials following it. Some of it may be preserved somewhere, but most may not be. This particular piece of the story was lucky enough to be maintained and cared for, deemed, by Robert Wilson and/or some other unnamed entity, to be important to the story of Gertrude Stein’s life and works.

Bibliography

“Saying Life. The Memoirs of Sir Francis Rose.” Beaux Books. https://www.beauxbooks.com/saying-life-the-memoirs-of-sir-francis-rose.html

“Sir Francis Rose.” England & Co Gallery. https://www.englandgallery.com/artists/artists_group/?mainId=164&media=Paintings

Stein, Gertrude. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas.First edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1933.