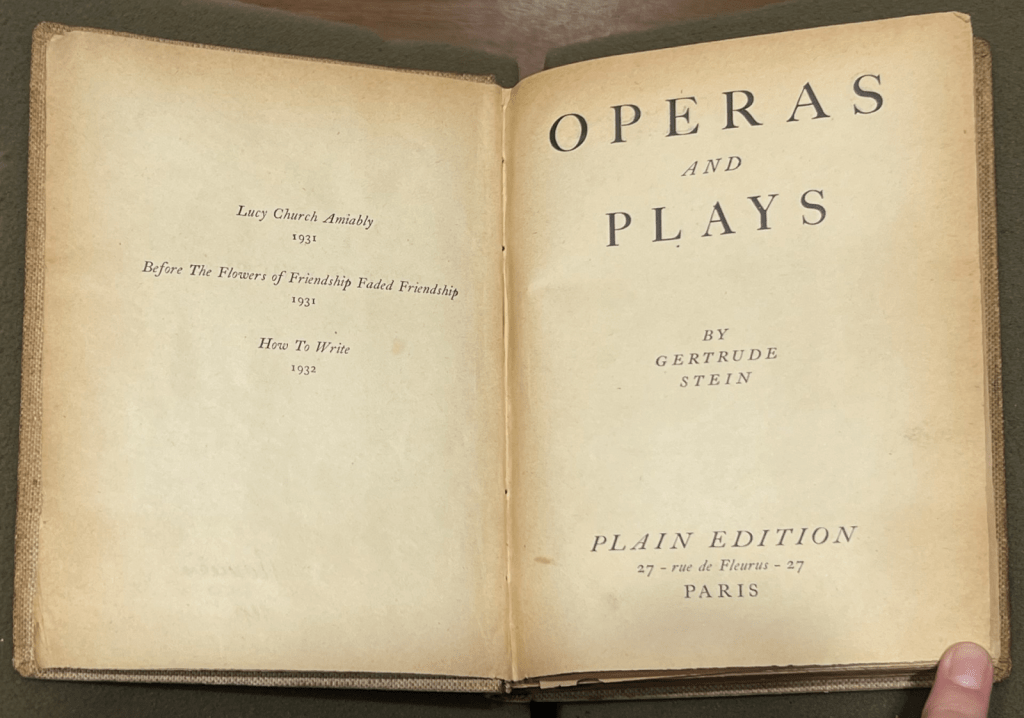

My sister recently published a novel and has spent the last two years learning the skills required for self-publication: editing, formatting, marketing, and more. After witnessing my sister’s escapades, I was interested in exploring Gertrude Stein’s own experiences with publishing her works. Between the years 1931 and 1933, Stein published five books with her partner Alice B. Toklas through a venture they called the Plain Edition, dedicated to publishing books of Stein’s unpublished writings. The Robert A. Wilson Collection includes a proof of the Plain Edition’s fourth publication, Operas and Plays (1932). Through the Operas and Plays proof, we can find some clues about Stein and Toklas’s publishing process. From archival records, we know that this particular proof was bound by Paul Bowles and was printed and inscribed by Maurice Darantiere. However, it is impossible to know many of the details about how this book was published as it was organized between Stein and Toklas who, as domestic partners, communicated mostly through conversation and notes instead of the letters between authors and editors that are sometimes found in archival literary collections. From editing my sister’s novel, I learned first-hand that editing is a long, multistep process that requires conversation between an editor and writer. The same way that my sister and I don’t have documentation discussing most of her revisions, Stein and Toklas have little to no documentation of conversations about the Plain Edition.

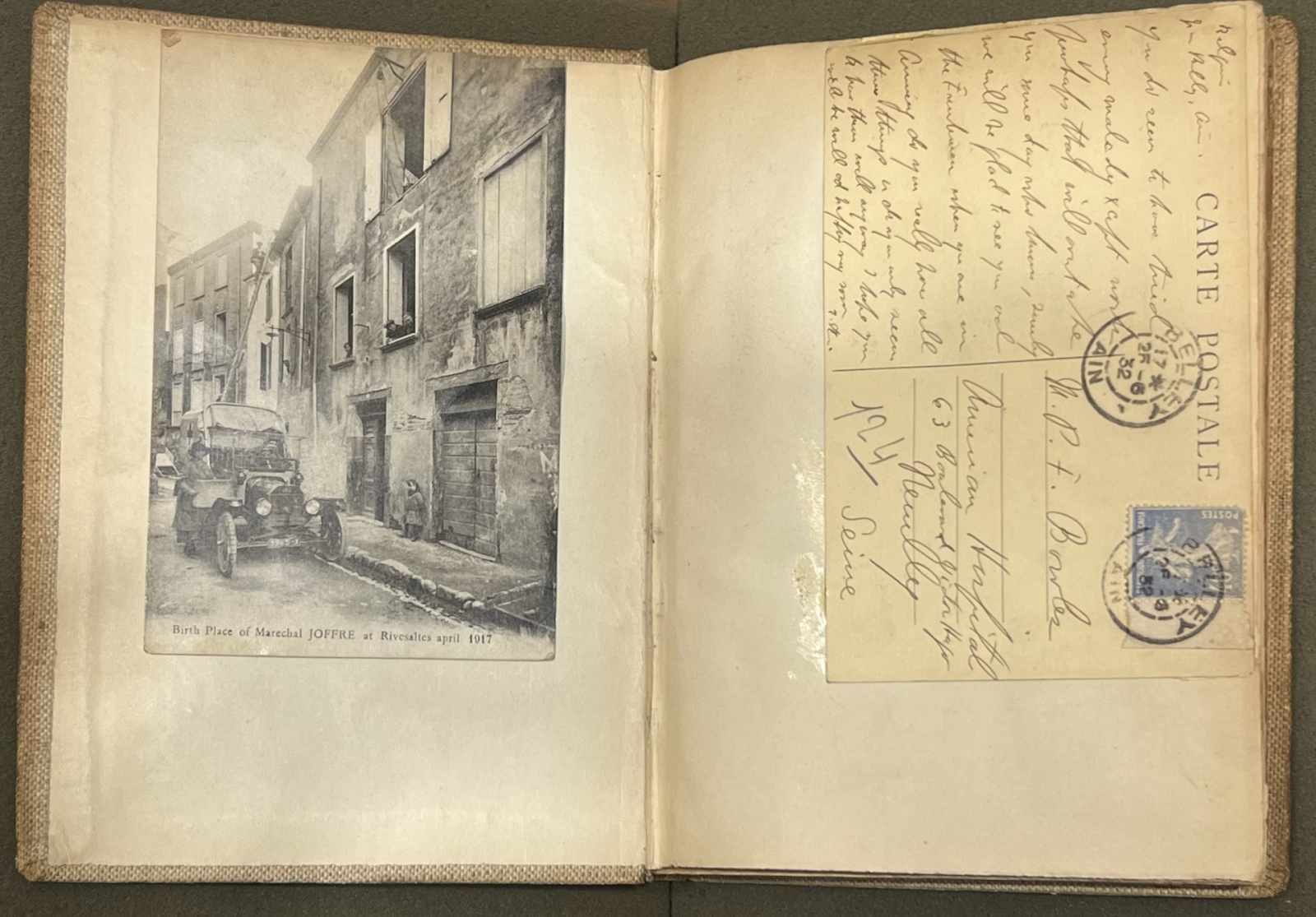

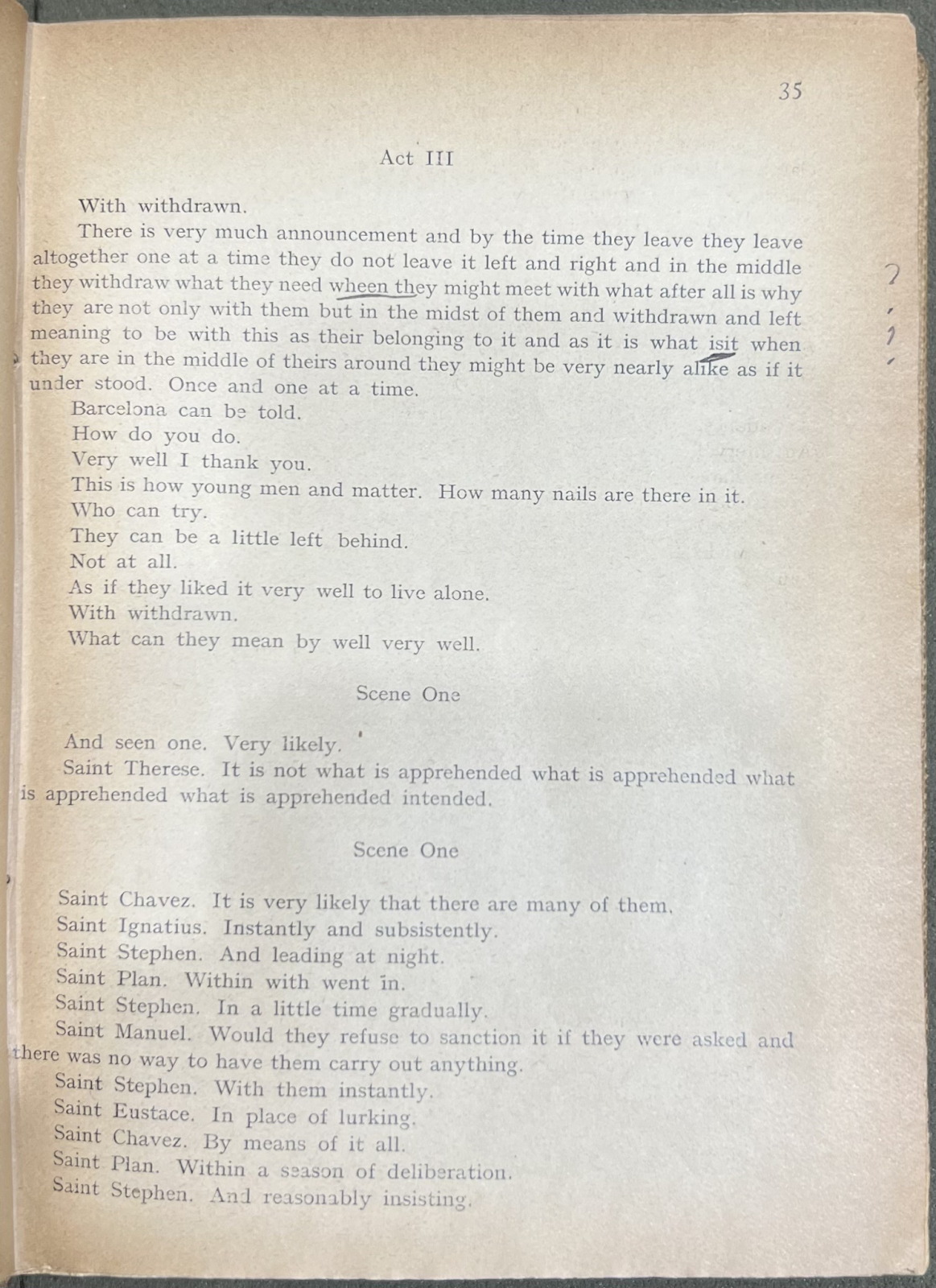

Operas and Plays was written by Stein and the transformation from a manuscript into a book was likely overseen primarily by Toklas and herself. After using a different printer for the first Plain Edition, Stein and Toklas decided to print the four later Plain Edition books, which included Operas and Plays, with Darantiere (Dean 23). His notes can be found throughout the book, which includes marks throughout the text signifying to fix printing errors (shown below). When binding the proof, Bowles included a postcard which is pasted onto the first page (shown below). The stamp on the postcard is dated June 25, 1932, which gives us an estimate of when this proof was printed in relation to the official publication later that year. This postcard also highlights how the Plain Edition was powered by Stein’s connections in Paris. The people with whom she worked to make these publications possible were not only her professional associates, but also (sometimes problematically) her friends. It is very possible that the complete list of collaborators who aided in the publication of Operas and Plays along with Stein’s other publications of the Plain Edition is not known. Those we know of are either credited in the printing or have documented correspondence with Stein or Toklas. However, it is possible that there were relationships and insights that were either undocumented on any sort of material, or for which any records of communication have been lost or destroyed. There could be many reasons for this, including Stein’s history of losing friendships over business or Toklas’s tendency to dispose of records documenting her involvement in Stein’s works. However, these are questions that will likely remain unanswered.

Image Captions

Postcard on front page of Gertrude Stein, Operas and Plays (Dijon: Plain Edition, 1932). From the Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. Photograph by Joelie Garcia. (Left).

Revisions for Four Saints in Three Acts from Gertrude Stein, Operas and Plays (Dijon: Plain Edition, 1932). From the Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University. Photograph by Joelie Garcia. (Right).

The most significant piece of information missing from and about this object is the discussions that must have taken place between Stein and Toklas. To some extent, we know the general motivation behind the Plain Edition. Stein had been struggling to reach the audiences she believed wanted to read her work. In many ways, she was frustrated that she could not reach her desired readership through traditional publication. Additionally, we are able to make some estimates about the costs of publishing Operas and Plays based on Darantiere’s original estimate for the printing of Lucy Church Amiably (1931) and with the knowledge that Stein and Toklas sold one of their Picasso’s to kickstart the Plain Edition (Dean 31). We don’t have exact receipts on the total costs or revenue from Operas and Plays, but we know enough that it was a significant financial investment for Stein and Toklas. In addition to questions related to the finances of the Plain Edition, we also don’t know how works were selected for publication. Stein had many more unpublished writings than the ones featured in Operas and Plays, but, as Stein and Toklas did not leave records of this discussion, we cannot know how they decided which works should be prioritized. As, in many ways, the Plain Edition was a business operated by Stein and Toklas, it is a bit strange that there isn’t a more thorough collection of financial records. However, considering that these books were published ninety years ago by two people who were essentially married, it is reasonable to understand how these documents never made it into the Wilson collection.

In terms of other conversations that Stein and Toklas may have had either about the business element of the Plain Edition or the contents of Operas and Plays, there is very little basis for us to make any assumptions. Yale’s collection of Gertrude Stein materials contains a quite impressive collection of notes left from Stein to Toklas and vice versa; one could easily spend hours sorting through the notes to find that they do not offer much insight on the topic. The purpose of an archival space is to use the connections between objects to present a story. Stein and Toklas likely had no idea that nearly a century after their publication of Operas and Plays, there would be inquiries about the specifics of their collaboration. And even if we had access to every note, letter, and receipt about the Plain Edition, we still wouldn’t know about what was discussed purely face to face. Archives offer information that can facilitate different interpretations; researchers use these archival materials to connect objects to people and ideas. Unanswered questions, such as Stein and Toklas’s conversations about the Plain Edition, are crucial to archival spaces because they are both a reason to expand a collection and the basis for which a collection is started in the first place.

Works Cited

Dean, “Make It Plain: Stein and Toklas Publish the Plain Edition,” from Primary Stein, 22–35.

Stein, Gertrude. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1933.

Operas and Plays by Gertrude Stein, Plain Edition page proofs (Dijon), 1932, Box: 5, Folder: 1. Robert A. Wilson collection of Gertrude Stein materials, MS-0785. Special Collections.