Gertrude Stein was many things: a novelist, poet, playwright, ambulance driver, publisher, and art collector. Most know her today as an eccentric lesbian who wrote eccentric books and kept eccentric company. Most do not know how deeply intertwined these aspects of her life were. Her friends, her writing, her art collecting, and her business were all connected. Perhaps no venture better exemplifies this dynamic than the production of Matisse Picasso and Gertrude Stein [G.M.P.] with Two Shorter Stories (fig. 1). Published through Stein and her partner Alice Toklas’s own publishing entity, which they called the “Plain Edition,” G.M.P shows how her friendships with other artists were mutually beneficial. To better understand these relationships, we turn to an edition of G.M.P. from the Robert A. Wilson Collection of Gertrude Stein Materials and the painting whose sale made the Plain Edition possible: Pablo Picasso’s 1905 Lady with a Fan (fig. 2). The close connection between these two objects reveal how in sync Stein and Picasso were in their artistic experiments and demonstrate how their friendship benefitted each artist not only creatively but economically as well. The eventual sale of Lady with a Fan reinforces this exchange.

G.M.P. consists of three short stories, all of which were in the making well before the book was published in 1933. Stein began writing the first of the three, A Long Gay Book, in 1909, Many Many Women in 1910, and G.M.P. in 1911. The stories were all completed by 1913 yet sat unpublished for twenty years. They are all written in Stein’s distinctive voice – a style that may seem daunting to the average reader, and certainly was daunting to publishers who couldn’t foresee turning a profit on these experimental works.

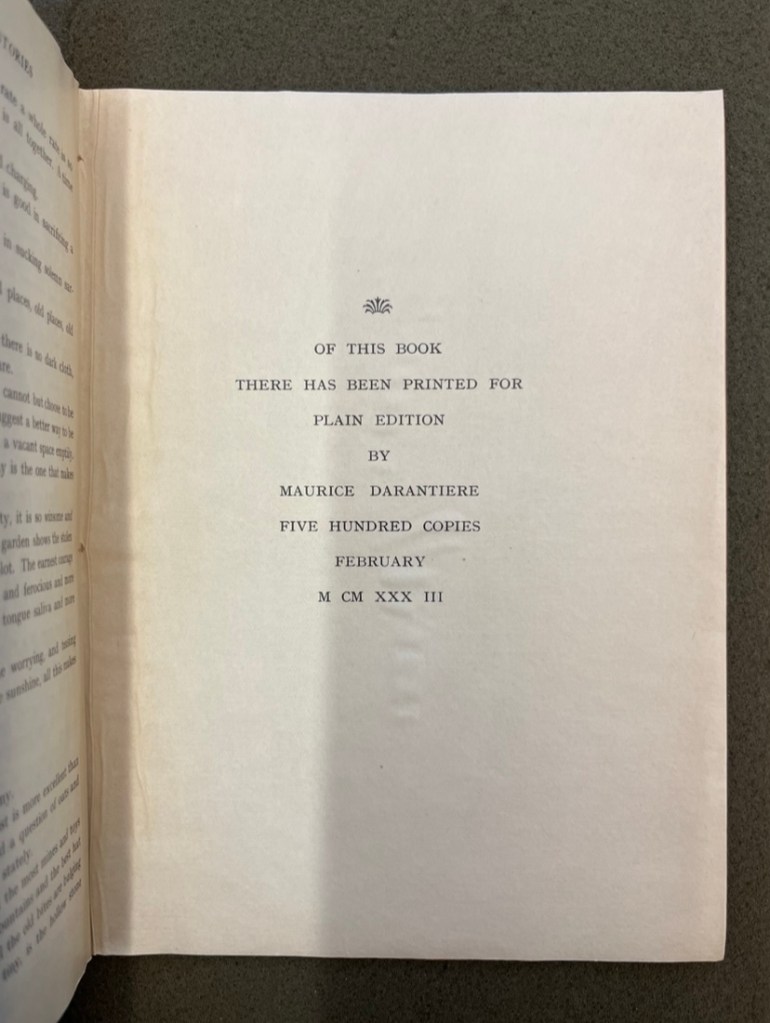

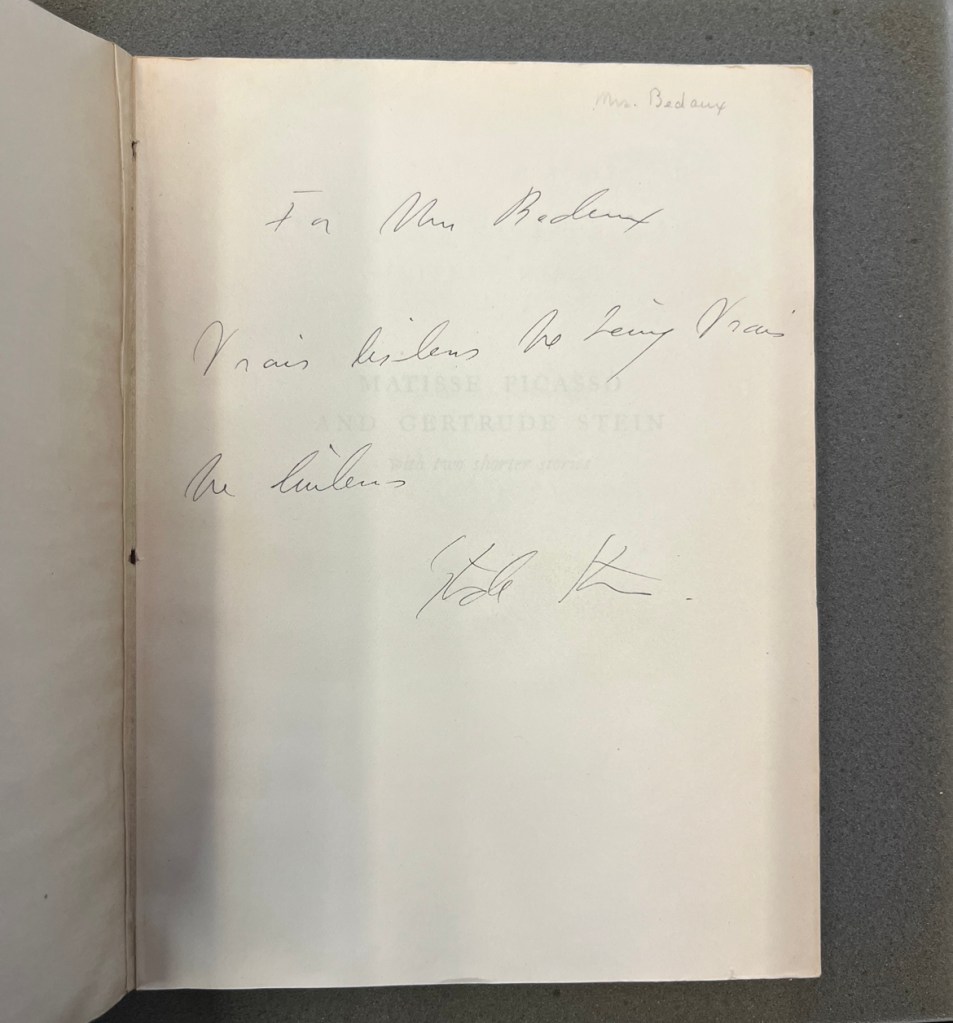

As Stein and Toklas created the Plain Edition on their own, they had to save money wherever possible in the printing process. G.M.P. is relatively small and the text fills up nearly all area on the pages (fig. 3). The book is bound in paper and, to make up for the fragility of the paper cover, published with a slip case featuring the title and author’s name on both the cover and spine of the box – likely a cheaper option than producing a full hardcover binding. The other four Plain Edition publications are listed across from the title page and on the last page it is noted that this is one of 500 copies printed by Maurice Darantiere, Stein’s printer and friend (fig. 4). On the inside of this copy, Stein has scribbled a dedication on the inside to a Mrs. Bedeux, evidently someone she wished to read the book (fig. 5).

Despite its prominence in the title, G.M.P is the last and shortest story in the book. Given the fame of both Matisse and Picasso, it’s understandable why Stein would choose to feature them in the title of the book. Her goal was to sell and to be read; the artists’ names alone garnered attention. In the title, Stein is of third importance. However, her name does appear twice on the cover – once in the title, and again as the author: “By Gertrude Stein” – she still made sure to make herself seen. The title is abbreviated in the headings of each page as G.M.P. and Two Shorter Stories – here, Stein puts herself first. Perhaps she simply thought the letters flowed better than M.P.G… More likely, she wanted to remind readers of her centrality to the text. This is Gertrude’s book – her words and hers alone – not Matisse’s nor Picasso’s.

Each story is a sort of literary portrait, with Stein looking to her circle of family and friends in A Long Gay Book, referencing people by pseudonyms, or looking towards women more generally in Many Many Women, using the pronoun “she” repeatedly to create a portrait of someone. Interestingly, the names of Picasso and Matisse never once appear anywhere in the text of the book. Instead, in G.M.P., Stein uses the pronoun “he” to refer to either man, creating a sort of dual sketch of the two men through this linguistic abstraction. Stein was fond of creating word portraits and did so often in her writings. Around the same time Stein was drafting G.M.P., she wrote two other short portraits of Picasso and Matisse that were published in Camera Works in 1912. Written in a similarly experimental style, they read more like substantial poems than narratives.

At the same time Stein was experimenting with new ways to depict an individual through text, artists in her circle such as Picasso were thinking of new ways to depict an individual through visual mediums.

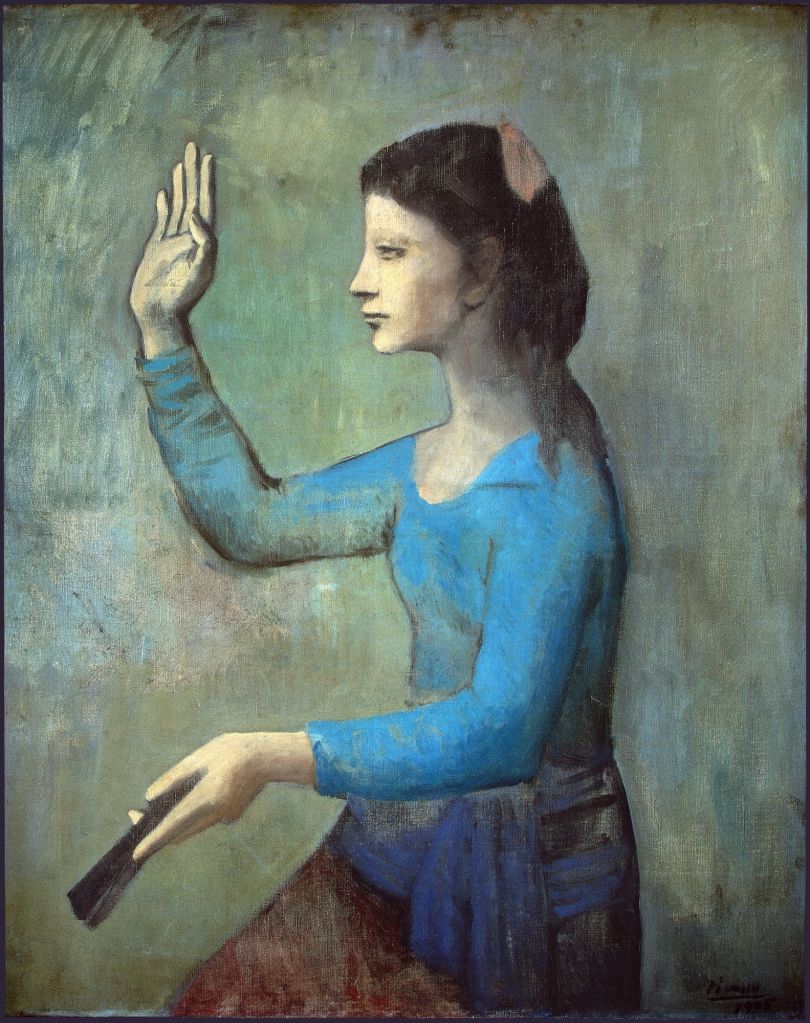

By 1913, Stein had acquired Lady with a Fan. Painted in 1905 during Picasso’s Rose Period, the piece marks an interesting shift in his style as he moved towards more abstraction and eventually, cubism. The titular lady’s face is unreadable, a cool mask that betrays little emotion. She raises her right hand either in greeting or goodbye. In her left, she holds a folded fan. Her features are angular, yet still significantly modeled. The stark washes of color and the sharp lines of her right hand hint at Picasso’s forthcoming development of cubism, yet this piece is still miles away from the abstraction he would soon reach. The odd pose is a departure from a preparatory sketch of the same subject (fig. 6), which shows the model sitting, with her right hand folded across her lap, blocking any movement from her left hand which holds the fan. By changing her pose in the painting, Picasso transforms his subject. He imbues her with an air of authority, dynamism, and energy. Why change his model this way? With the gesture of the arm, an implied observer is introduced. During this period and his preceding Blue Period, Picasso frequently depicted solitary figures, often in profile, yet the active communication with a figure just beyond the boundaries of the canvas was something new.

Art historians have often categorized Picasso’s works of the preceding Blue Period as having a sense of somber melancholy. In contrast, works made in the Rose Period display images of strength and agility, with bodily forms reaching out, stretching across the canvases, and expanding to take command of the piece. Many pieces retain some sense of melancholy, mainly through facial expressions that convey a particularly austere mood, such as in Lady with a Fan. Picasso significantly expands on this dynamism in his experiments with cubism; in Demoiselles d’Avignon, familiar postures are radically revised, their forms manipulated into seemingly new ways of depicting human bodies – notably inspired by African and indigenous Iberian sculpture. Picasso himself is reflected in his works, as all artists are; his evolution as an artist mimics how his subjects gain more and more agency in his works, from the Blue Period to the Rose Period and through Cubism. His increasing confidence in his genius and experimentations can be read on the canvases over time.

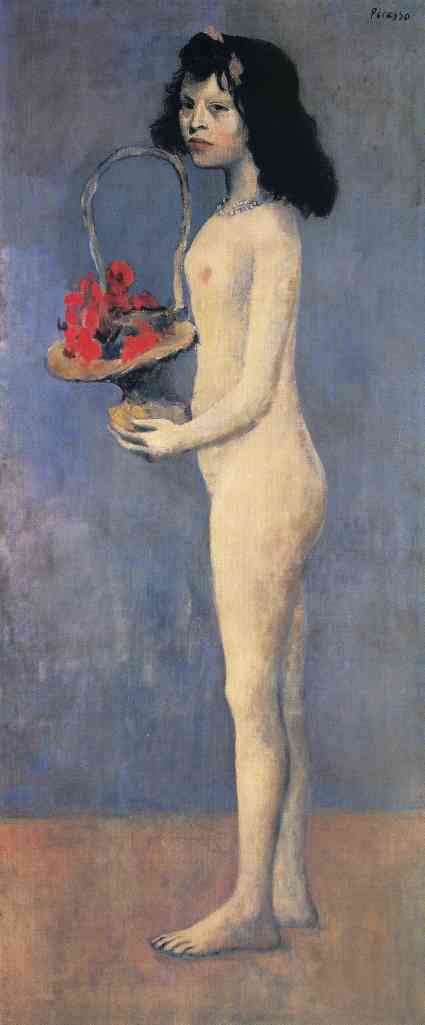

When Stein purchased Lady with a Fan in or before 1913, she and her brother Leo had already acquired numerous Picasso pieces, including distinctly cubist works, such as The Architect’s Table. Records show that in May of 1912 Stein purchased two additional cubist still life paintings. Her love of Picasso’s work went beyond stylistic periods; she wasn’t necessarily interested in his development but enjoyed and collected his art in all of its forms. Leo, on the other hand, preferred his more figural pieces and left all the Picasso’s in their collection to his sister when he moved out of 12 Rue de Fleurus. When Stein sold Lady with a Fan in 1931 through the art dealer Paul Rosenberg, she and Alice still retained pieces from all periods of Picasso’s work. She didn’t choose to get rid of the piece for any obvious stylistic reasons; for example, Fillette nue au panier de fleurs (Nude Girl with Basket of Flowers), painted in a similar style,(which Stein famously hated when she and her brother first purchased it) remained in their collection (fig. 7). Unfortunately, Stein and Toklas did not preserve any correspondence that would reveal how much they got from the sale of Lady with a Fan and how much of it they spent on producing the Plain Edition. By 1931 Picasso was a household name so the value must have increased significantly from when Stein purchased it. Potentially there was an economic motivation for the selection, but it’s impossible to say whether it was any more valuable than other Picassos in their collection.

Given the proximity in which Stein acquired Lady with a Fan and composed G.M.P. with Two Shorter Stories, perhaps she felt an innate connection between the two works. Both the painting and the literary portraits are exemplary of two distinct moments in the artists’ respective careers. Picasso and Stein, in coming into their own style and voice, experimented with their mediums to push their creativity and produce reflections of themselves. Picasso, in extending the limbs of his model and asserting an authority in the work predicts his development into his even more experimental cubism. G.M.P. and Two Shorter Stories is the culmination of Stein’s experiments with word portraits, reflecting her own interest in human psychology and manipulating the English language in wholly original ways. Two geniuses, at pivotal moments in their careers – only Stein couldn’t be recognized as such without the acknowledgment of the public, and thus G.M.P. was only published years later when she had the means to do so herself, thanks to the sale of Lady with a Fan.

By selling a Picasso in order to finance her writing career, Stein reinforced the importance of that friendship, prolonging the relationship rather than disavowing or insulting it. Through their decades long friendship, each artist grew, and their respective careers benefitted because of it.

Bibliography

Dean, Gabrielle. “Make It Plain: Stein and Toklas Publish the Plain Edition.” In Primary Stein: Returning to the Writing of Gertrude Stein, edited by Janet Boyd and Sharon J. Kirsch, 13-35. United States: Lexington Books, 2014.

Giroud, Vincent. “Picasso and Gertrude Stein.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 64, no. 3 (2007): 1–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25434126.

Lubow, Arthur. “An Eye for Genius: The Collections of Gertrude and Leo Stein.” Smithsonian Magazine. January 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/an-eye-for-genius-the-collections-of-gertrude-and-leo-stein-6210565/

Mallen, Enrique. “Reaching for Success: Picasso’s Rise in the Market (The First Two Decades).” Arts 6, no. 2 (2017): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts6020004

Schapiro, Meyer. Modern Art, 19th & 20th Centuries: Selected Papers. New York: G. Braziller, 1979.

Voorhies, James. “Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pica/hd_pica.htm