Throughout her life, Gertrude Stein had several close friends who doubled as colleagues within the modernist art and literary movement. Mabel Dodge Luhan, a fellow American writer and a famous author in her own right, became a friend of Stein’s during a brief visit to 27 rue de Fleurus in the spring of 1911. Their bond was cemented later that year when Gertrude Stein, Alice Toklas, and Leo Stein, Gertrude’s brother, visited Dodge’s villa near Florence. In subsequent years, the two women wrote about and described each other, responding to and boosting each other’s works. Through this reciprocal appreciation, Stein and Dodge created a relationship that provided professional and social benefits. Two artifacts that provide insight into their “mutual admiration society” are A Portrait of Mabel Dodge by Gertrude Stein and “Speculations, or Post-Impressionism in Prose” by Mabel Dodge.

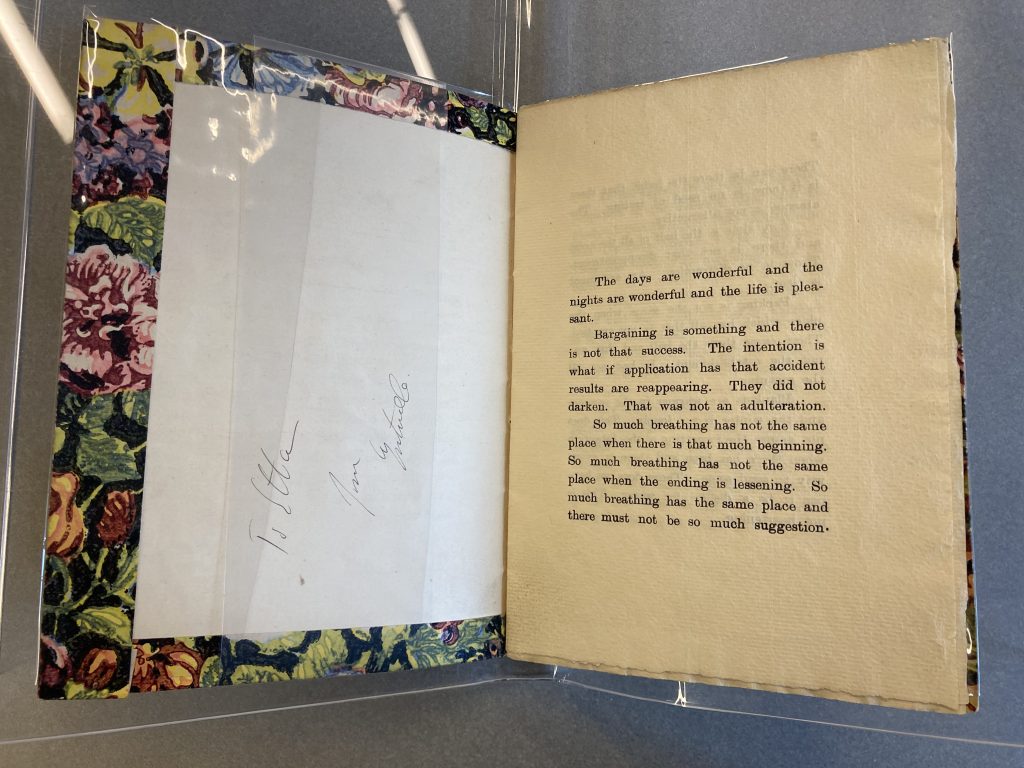

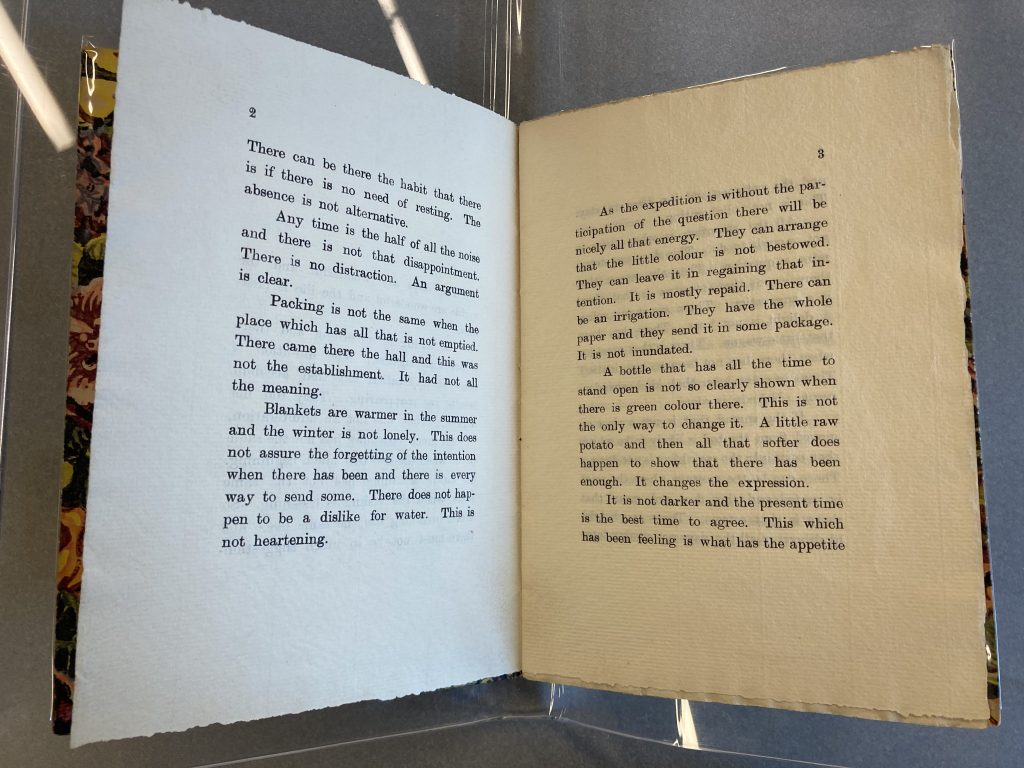

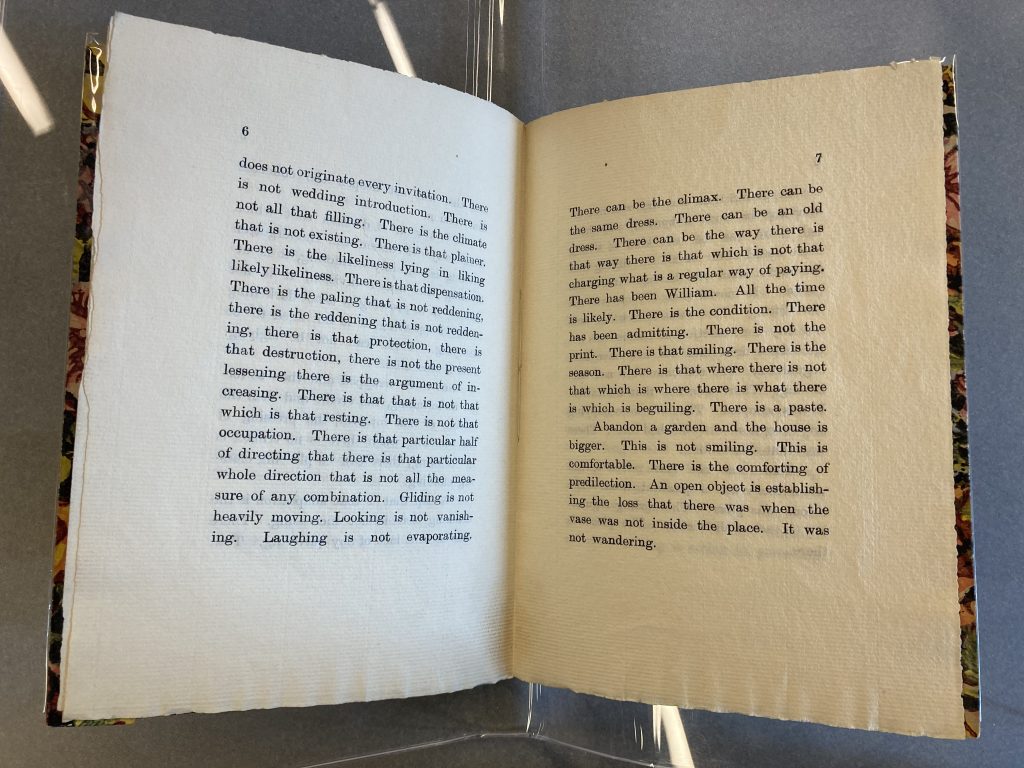

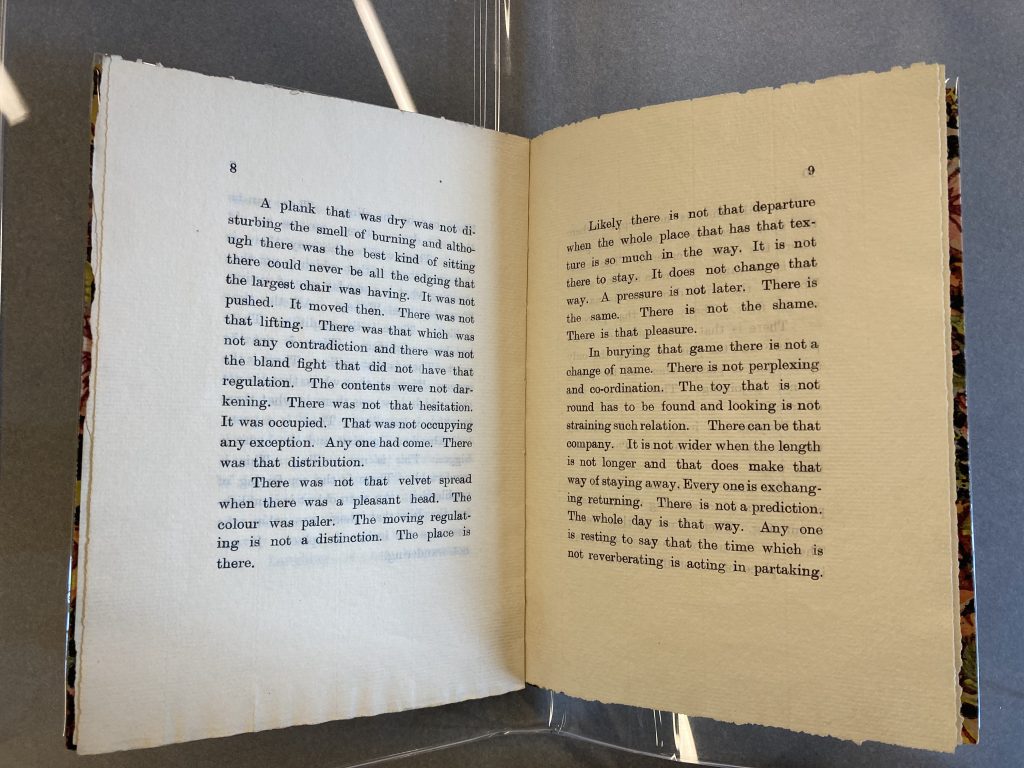

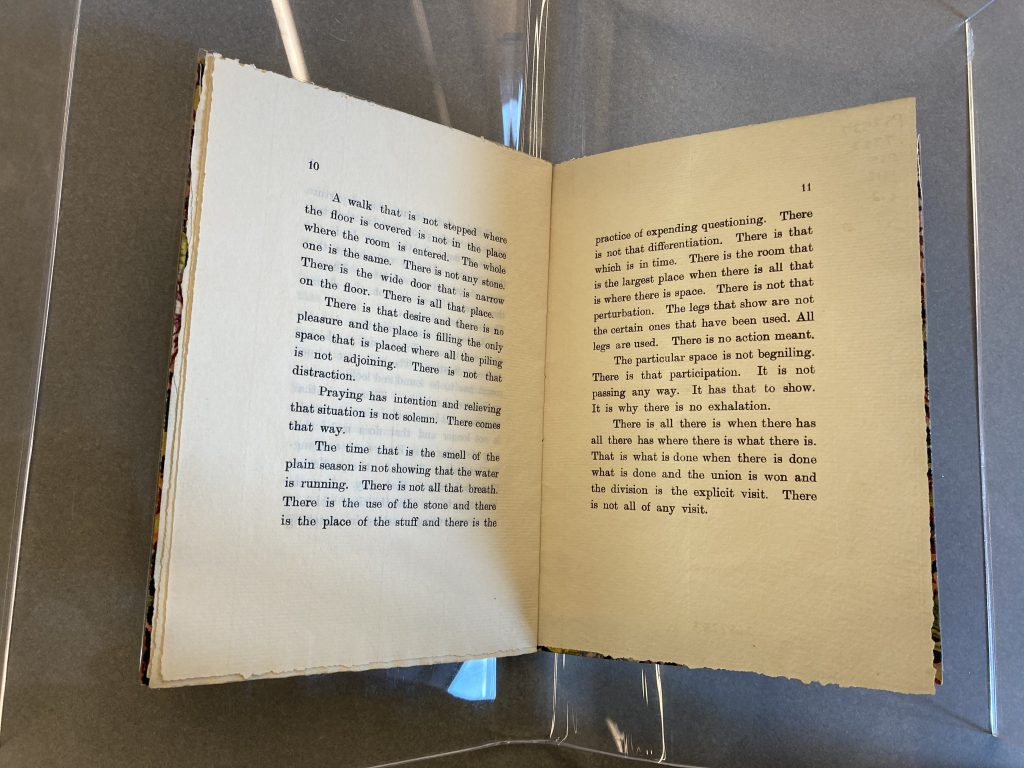

During her visit to Florence in 1911, Gertrude Stein wrote a portrait of Mabel Dodge. Stein often used this “portrait” technique to describe her friends, going beyond just creating an image in words but working to “[produce] a coherent totality through a series of impressions” (Dodge 173). The Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia focuses on Dodge as she was during a well-known affair with her son’s tutor (Dixon Donnelly), shown through the sensuous tone and suggestive lines Stein included, such as “Abandon a garden and the house is bigger … This is comfortable. There is the comforting of predilection” (Stein 7). Dodge claimed to have a flirtatious relationship with Stein and, in her memoir Movers and Shakers, described their connection, which Toklas severed after that summer (Dixon Donnelly). In early 1912, Dodge moved back to America, and Stein later sent her a copy of the finished portrait filled with little nods to their summer together. Mabel reportedly fell in love with the written portrait and went about getting it published (About Mabel). The small chapbook was privately published in 1912 with Florentine wallpaper for book cloth and 11 pages strictly dedicated to the text with no publisher named or copyright page included. The publication of the portrait as a small book meant, for Stein, that another of her works was published – a dearly held aim; for Dodge, it meant that she could connect her name as an up-and-coming member of the post-Impressionist movement with the name of a well-known collector and modernist figure.

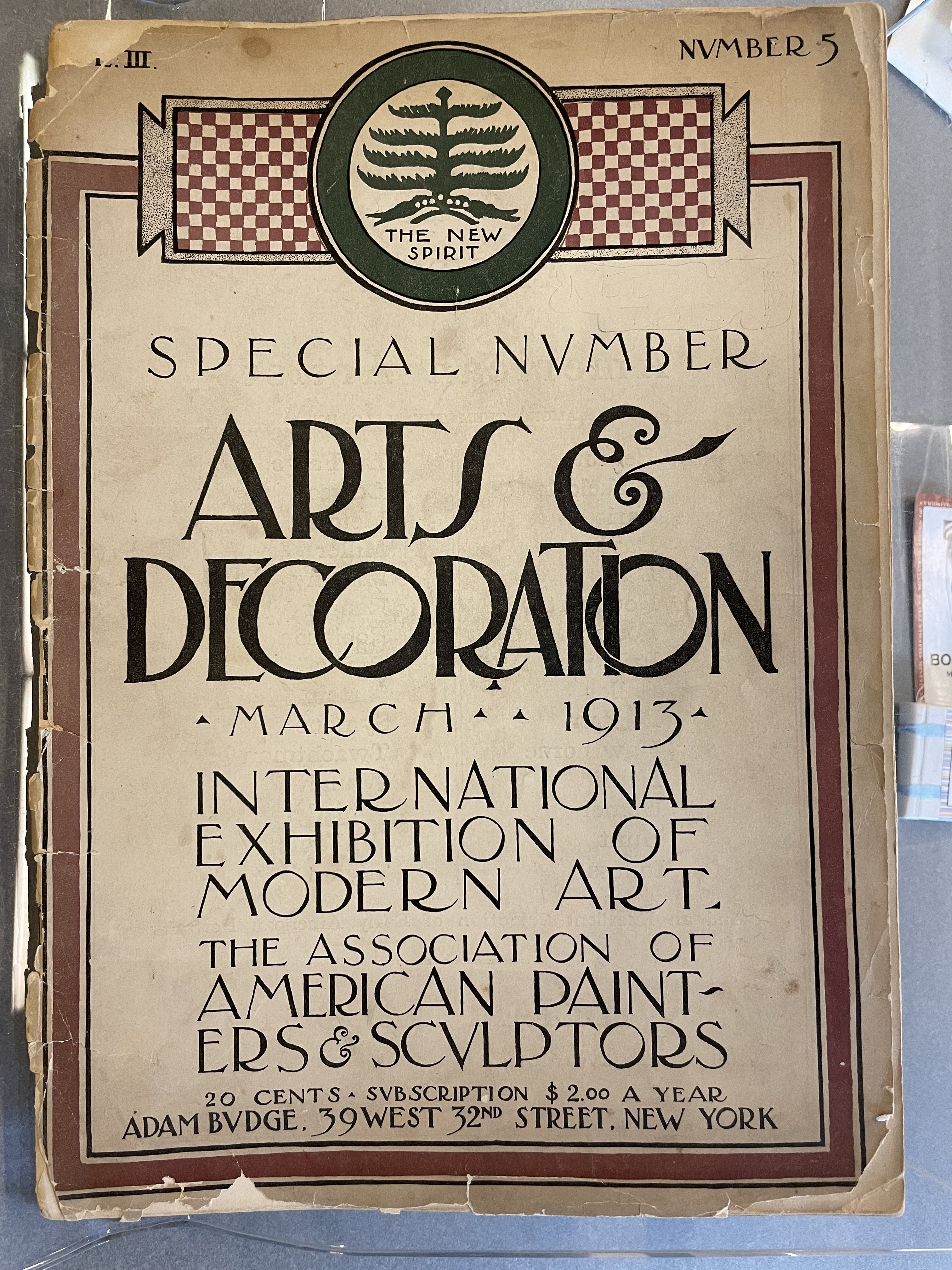

The following year, on the other side of the pond, Mabel Dodge Luhan started her well-known salon in New York and became a prominent figure in both the political and art worlds. In 1913, Dodge was asked to write on Gertrude’s works, resulting in the article “Speculations, or Post-Impressionism in Prose,” published in the magazine Arts & Decoration. This article describes the characteristics of Stein’s writing and its connection to the cubism movement led by Stein’s close friends Picasso and Matisse. For two pages, Dodge praises Stein’s unique methods of writing that, in her opinion, had shifted written descriptions into ‘impressionistic writing’ that created the same sense of ‘the hidden and inner nature of nature’ as the cubist artists made through their paintings (Dodge 172). Within her article, Dodge calls attention to her portrait by Stein by quoting from the work, providing evidence for Stein’s revolutionary technique. In particular, this included the abstraction at the sentence level that, when read alone, didn’t make sense but, when connected to the larger piece, worked to produce a set of feelings rather than a specific story or clear image.

Arts and Decoration was a widely circulated magazine published from 1910 to 1942, so Dodge’s article was actually much more accessible to readers than Stein’s actual portraits—which, in 1913, only existed in published form in the limited-edition Mabel Dodge chapbook and portraits of Matisse and Picasso in the specialist magazine Camera Work in 1912. These differences in access provide essential information about the intended audience for each piece and the purpose behind their publishing. The portrait was published in a limited run by Dodge after receiving the manuscript as a gift from Stein. The short book provided limited information on the making of the text, with only the title and author listed and no copyright or publication details added. Alternatively, Dodge’s articles’ inclusion in a large and popular magazine came with other articles of prominent figures in the arts scene, both artists and salon hosts such as Dodge. The magazine also included photos of works by the artists mentioned in Dodge’s article, including Picasso and Matisse. Included on the article’s first page is a reproduction of a photograph of the sculpture Portrait of Mademoiselle Pognay by Constantin Brancusi, which at first glance may seem unrelated but in fact expresses, in another medium, some of the same artistic practices mastered by Picasso, Matisse, and Stein. These aspects of the magazine promoted a wider readership by having a larger publication run, images, and multiple articles included in one source.

Through her article, Dodge perpetuates the idea of the “great” Gertrude Stein, describing her practice of only writing at night and waiting for the perfect word to come to her (Dodge 172). In 1913, Stein was becoming known to audiences in the United States through newspaper stories that sometimes parodied or criticized her repetitious writing techniques, and sometimes praised her unique style. However, Stein was also gaining recognition as an artistic celebrity, and was given different personas by the media, including the strong, stoic female author and the contemplative and languid genius (Anderson 6). Dodge’s article continues and feeds the idea of a stoic Gertrude sitting by the fire at night, thinking of perfect words for her next groundbreaking piece. Building up Stein’s mystique and a “cult of personality” might have helped to promote Stein as a member of this artistic crowd of modernist free thinkers who devoted themselves to their work.

As these women wrote about each other, they simultaneously expressed their friendship and helped each other’s literary careers. The nature of the bond they shared was public, as is evident in an Editor’s Note that accompanies Mabel Dodge’s article: “This article is about the only woman in the world who has put the spirit of post-impressionism into prose and written by the only woman in America who fully understands it” (172). Mabel Dodge’s comprehension of Gertrude Stein put her into a select, special group, including Stein’s life partner, Alice B. Toklas, and her close friends Picasso and Matisse. In this relationship, these women were able to work together and support each other’s work throughout their careers. While Stein has been shown to work closely with those she deemed geniuses—the majority of whom were male—this bond shows the rare occurrence of a professionally beneficial relationship she formed with another woman.

Bibliography

“About Mabel.” The Mabel Dodge Luhan House, http://www.mabeldodgeluhan.com/history/about-mabel/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2023.

Anderson, Sherwood. Forward. Geography and Plays, by Gertrude Stein, New York; Something Else Press, 1968. Print.

Dixon Donnelly, Kathleen. “Mabel Dodge and Gertrude Stein.” Edited by Clêr Lewis, Something Rhymed, 4 June 2018, somethingrhymed.com/category/mabel-dodge-and-gertrude-stein/.

Luhan, Mabel Dodge, and Robert A. (Robert Alfred) Wilson. “Speculations : or Post-Impressionism in Prose.” Speculations : or Post-Impressionism in Prose. N.p., 1913. Print.

Rudnick, Lois P. “Radical Visions of Art and Self in the 20th Century: Mabel Dodge and Gertrude Stein.” Modern language studies 12.4 (1982): 51–63. Web.

Stein, Gertrude, and Robert A. (Robert Alfred) Wilson. Portrait of Mabel Dodge at the Villa Curonia. Florence: [Publisher not identified], 1912. Print.