Gertrude Stein is perhaps best known for three things: her flair as an art collector, her authorship, and the company she kept. This set of page proofs from the Robert A. Wilson Collection of Gertrude Stein Materials at Johns Hopkins University’s Sheridan Libraries exemplifies who Gertrude Stein was as an author: a force of nature. The pages are uncorrected proofs (save for the title – but we’ll get to that later) for the book that was published in 1931 as How to Write. They contain a mere fragment of Stein’s musings on the craft of writing. Known for her eccentric and distinctive use of language, the text of How to Write offers her “instructions” – I use that word loosely – on how to write in her manner. The result, in typical Stein fashion, seems repetitive, disconnected, rhythmic, and is an utter dismissal of typical writing conventions.

Though small in size and few in number, these pages offer incredible insight into how Stein perceived her own talents and considered her position in the world of literature and publication. They demonstrate her confidence in her own genius and her determination that others recognize it as well.

The page proofs bear the printed title Saving the Sentence. Knowing Stein’s adamant faith in her own talent, as well as her penchant for humor, this title seems apt. Stein regarded herself as a true genius and wanted readers to know that her literary experiments predated those of better-known male authors such as James Joyce. Joyce and others were celebrated for their creativity and innovation in their own time while it took decades for Stein’s impact on literature to be fully recognized.

Struggling to be taken seriously by publishers and the public, Stein, with her partner Alice Toklas, decided to further forgo the conventional routes to publication with the creation of their own publishing entity, what they called the “Plain Edition,” through which they published five of Stein’s works between 1930 and 1933. How to Write was the third title to go to print. A costly undertaking, she and Alice sold one of their beloved Picasso paintings to fund the venture. Her innovative, if odd, writing techniques caused many errors in the printings of her works by larger publishers. With this independent venture, Stein had full control over what went into her books. These page proofs display Stein’s untainted vision for her book’s design.

The front cover displays the title in capital letters and nothing else, save for a faded hand-written message at the top (fig. 1). In Stein’s own hand, the message is basically illegible. She likely inscribed it as a dedication to a friend – the name Kitty can be deciphered at the beginning of the message. Whether or not Kitty actually read it is unknown.

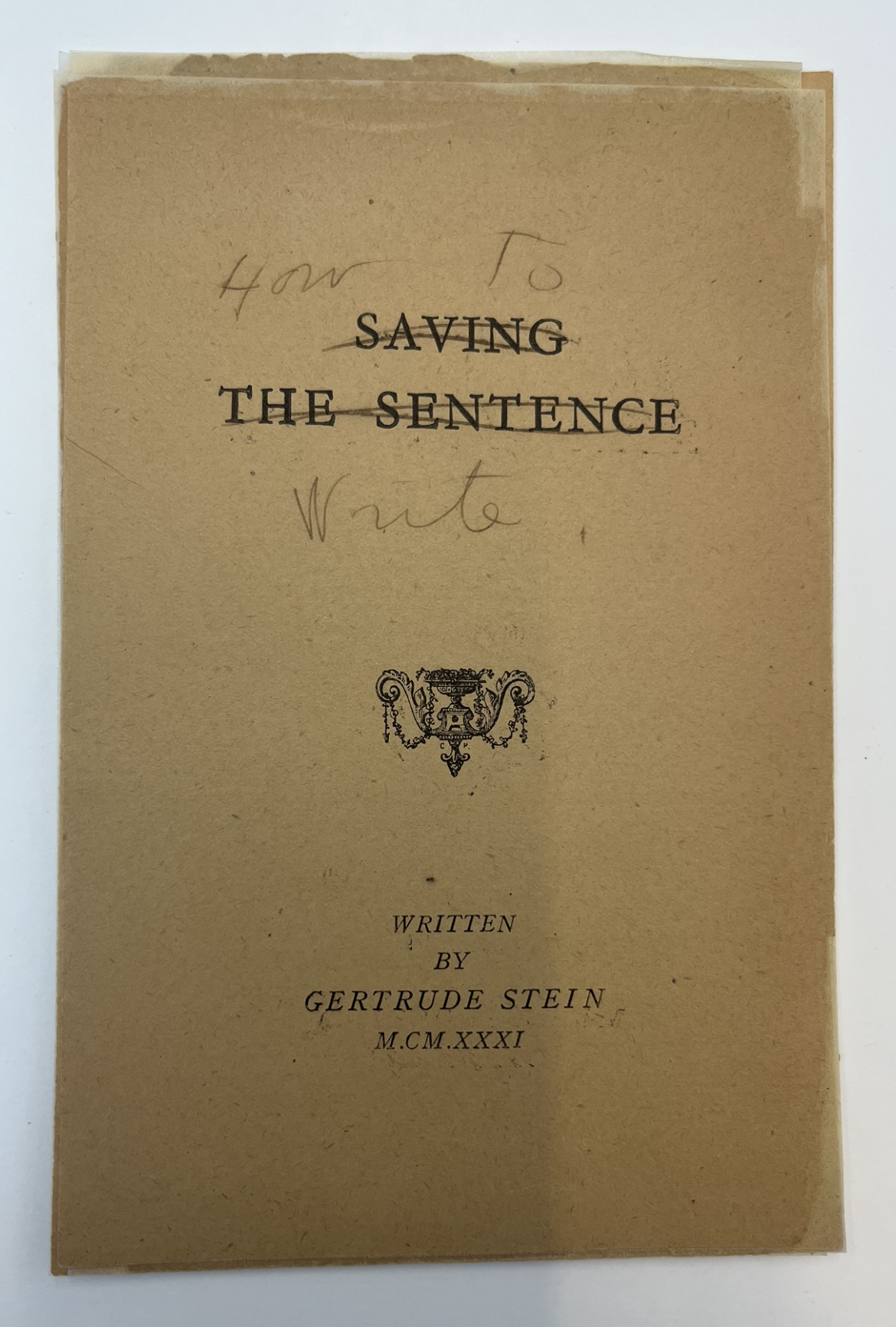

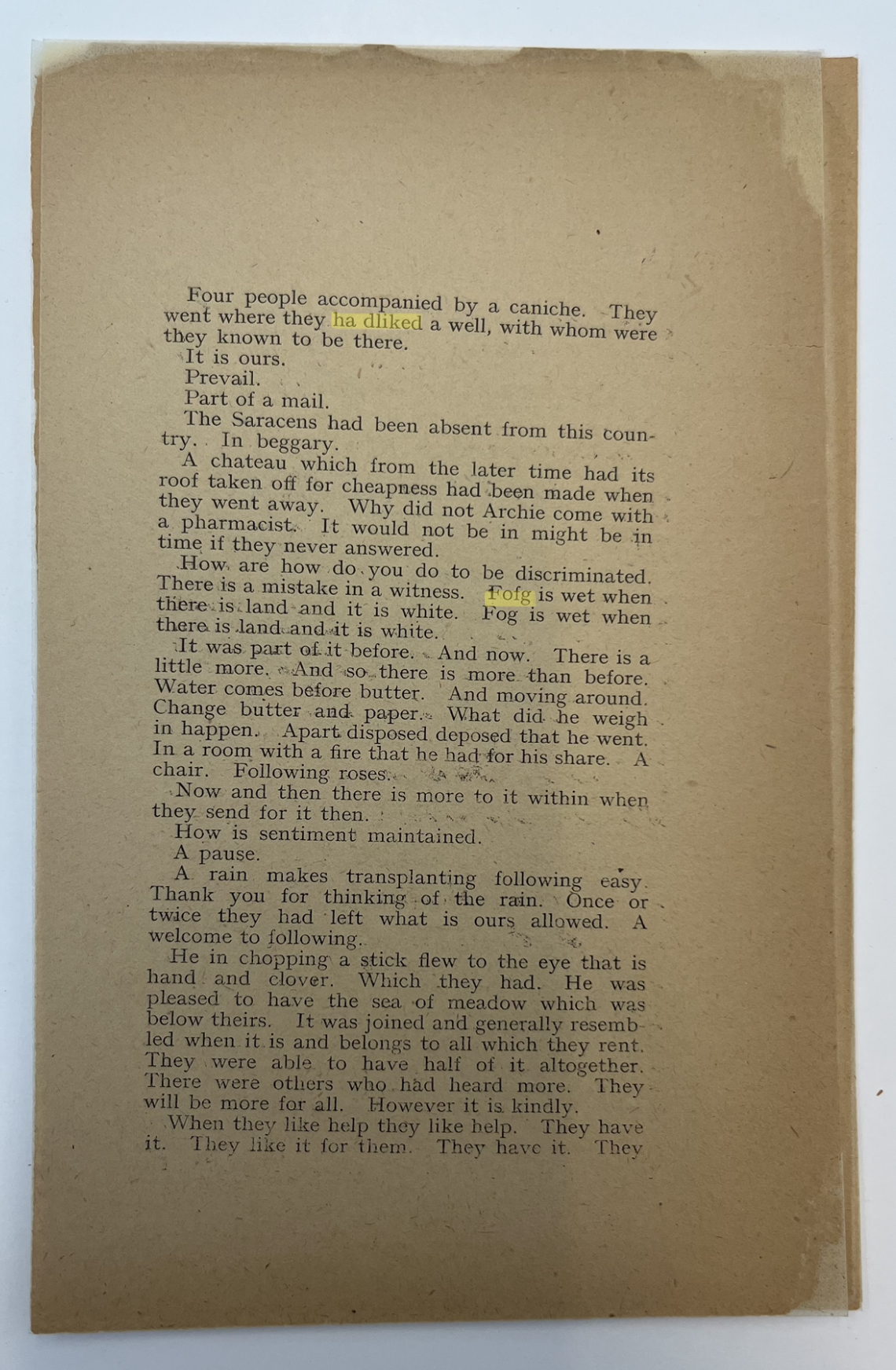

Turning to the title page, the words Saving the Sentence have been crossed out decisively in pencil and Stein has written in by hand the title this work is now known by: How to Write (fig. 2). Still three words long, How to Write expresses a significantly different approach to the book than Saving the Sentence. The new title conveys the idea of an instruction manual – something a high school English teacher might put on the syllabus. If you were to pick up How to Write, you might expect a straightforward step-by-step approach to composition, outlining sentence structures, grammar rules, and the like. You would be sorely disappointed. Stein, stubborn as ever, does not sway from her unusual sentence patterns. On the first page, she writes: “What is a sentence. A sentence is a part of a speech. A speech. They knew that beside beside is a colored like a word beside why there they went.” (fig. 3). Unless a reader is fluent in Stein’s language, any meaning from this string of words is difficult to detect. Perhaps the best way to learn how to write like Stein is simply to read her – she seems to think so.

The title page design itself is simple, one might even say “plain,” as the edition’s name promises, including only the title (and its revision), the authorship, the date in roman numerals, and a small seal representing the Plain Edition close to the center of the page. Once again, Stein forgoes publishing conventions: instead of simply providing her name as author, she has had printed “Written by Gertrude Stein.” This curious choice could be taken as a play on the title, yet it was chosen before the revision was inscribed. More likely it serves a reinforcement of her authorship. Stein wanted, perhaps needed, for readers to first and foremost consider her as a serious author, rather than the enigmatic celebrity/writer/personality she was becoming (soon to be made into a household name, thanks to the 1934 lecture tour in America). This small decision indicates that even at the most basic level of literary convention—what you put on a title page—Stein was interested in making interventions.

An examination of the pages that follow shows that the simple design style of the title page has been carried through. The text appears uncrowded with relatively wide margins. The pages as a set are rather small; the smaller and lighter the book, the cheaper it was to print and the easier it was to circulate.

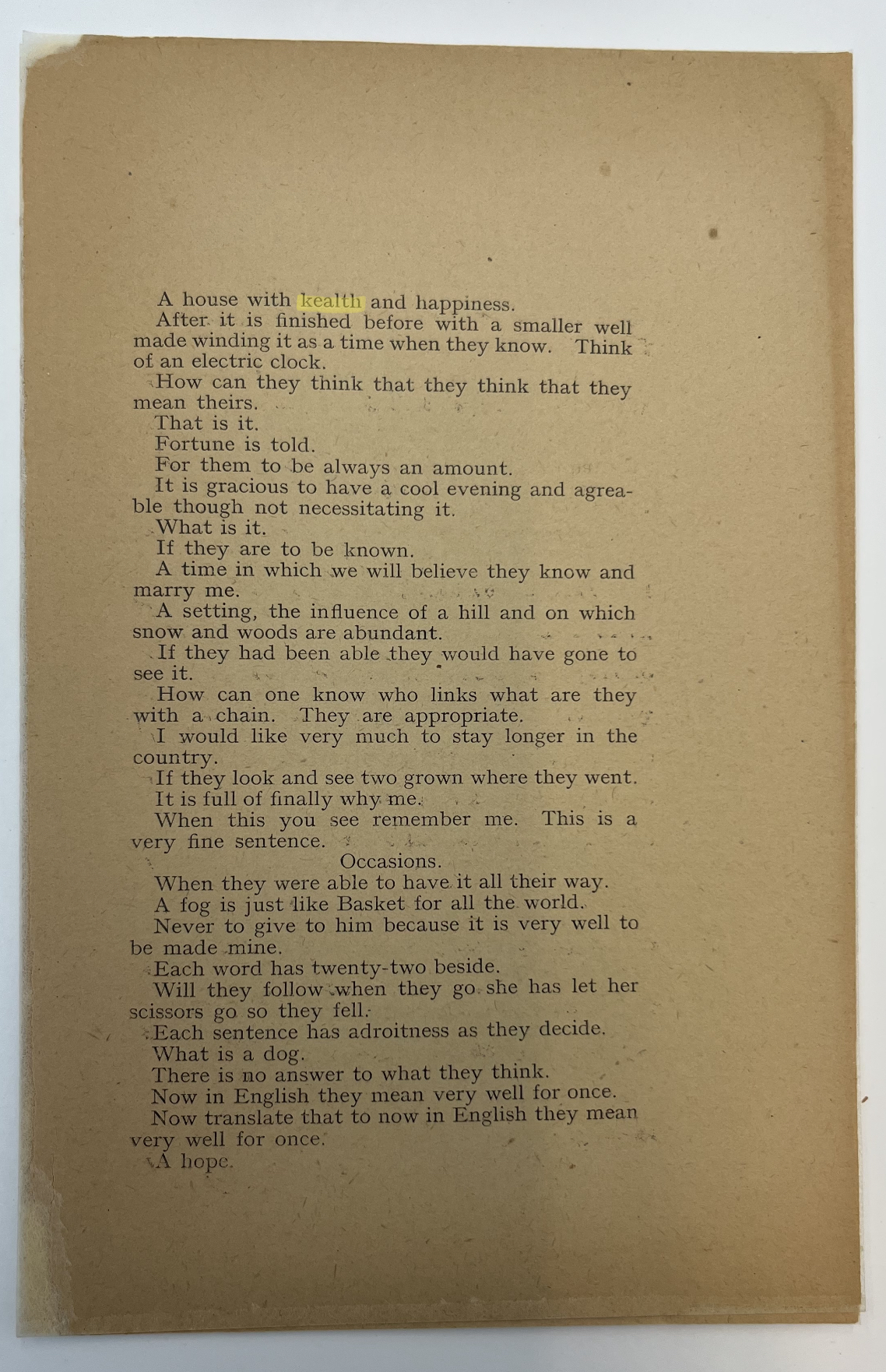

Given Stein’s unconventional style, it’s difficult to determine, when reading these proofs, if a misplaced or missing comma was the result of the printing or an intended lapse. The page proofs do contain a few glaring typesetting errors: “ha dliked [had liked],” “fofg [fog],” (fig. 4) and “kealth [health]” (fig. 5). Other than her emendation of the title, it appears that Stein did not correct this set of proofs. The question is: why not? She took the time to amend the title, suggesting that she did in fact care about the proofs and intended them to be read. The eventual publication of the text indicates that there was at one point another set of corrected proofs fixing the glaring errors. However, the Beinecke Library at Yale, which has the largest collection of Stein manuscripts, does not possess page proofs for this text, making it difficult to determine where, if anywhere, they might exist or what they might tell us about Stein’s editing process.

Stein’s brief venture into publishing and her interactions with these page proofs demonstrate her steadfast conviction in her own talent and worthiness of being read. The fact that someone cared enough to preserve these few pages for nearly 100 years is a testament to her prolonged impact on literature. While the pages themselves don’t necessarily prove her genius, their preservation shows us someone must have believed so.

See https://archivesspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/174501 for object details.